Water Conservation in the Garden

This article covers what I consider the top 5 ways to conserve water in the garden:

1) rain barrels (or other rain catchment system);

2) mulching;

3) plant selection;

4) drip irrigation; and

5) shaping the land with berms and swales or hügelkultur mounds.

Rain Barrels

If you’re tied into a municipal water supply (i.e., not a well), you pay your municipality for premium, clean water that you spray on the ground for your plants. When it rains, free water drains away into the municipal storm drain. You pay to use the water, and you pay (through taxes) to get rid of the excess water. If you live in an urban or suburban area and have access to a roof and the ability to tie into a gutter, it makes so much sense to invest in a rain barrel. If you have the space, you could also install a larger system than rain barrels, including underground cisterns or other large rain catchment systems. Rain barrels can also be installed on lean-to’s and small sheds, and in this way are becoming more common in community gardens.

There is an upfront cost to rain barrels, but some municipalities have a rebate program to help with the cost. I have two 1000-litre rain barrels that cost about $700 each, but my municipality rebated $600 of that (per barrel). There is also a huge range of rain barrel options to choose from at all different price points, and it’s usually easy to find them used.

You can also retrofit anything that holds water and turn it into a rain barrel.

When installing your rain barrel, I recommend elevating it so gravity helps give you better water pressure. You can build a wooden stand or put it on concrete blocks – there’s a way to do it for any skill-level.

Mulch

You may have heard the adage, “the Earth is modest, she likes to be covered.” You’ll see this in practice when you leave a patch of bare earth unattended. It will quickly grow over with weeds (opportunistic plants who don’t need your help to survive). Bare soil – especially soil that has been tilled or worked up – is a surface that water (and carbon) can more easily escape from. By covering it with living plants or mulch, two main things happen that conserve water: 1) the moisture in the soil is protected from evaporation, 2) organic matter breaks down into spongey “loam” that is excellent at holding onto excess moisture, releasing it as plant roots need it.

There are so many amazing mulch options. My personal favourites are chopped straw for annual vegetables, and wood chips for deep-rooted perennials. You should never have to pay for woodchips (unless you need them RIGHT AWAY). I use ChipDrop to arrange connections with local arborists, and have also made my own connections with arborists. Arborists have to pay a dumping fee to dispose of the chips from a day’s work. When residents are willing to let them dump the chips in a driveway, it saves everyone money. The woodchips from arborists are usually excellent for the garden because they contain mixed sizes and species of wood, including leaves and coniferous needles. These materials feed the soil life a balanced diet.

One thing to note about woodchip mulch is that it can tie up the nitrogen in the surface layer of the soil as it decomposes. As long as you’re mulching plants whose roots go deep, it won’t bother them. Just don’t try sowing annual vegetable seeds or growing shallow-rooted seedlings under a layer of fresh woodchip mulch. Once the wood chips have broken down, though, the soil will be amazingly nutritious and fluffy for planting whatever you want.

Other organic mulch options include:

- Raw wool (if you happen to have sheep or a shepherd friend)

- Old hay or straw

- Weeds and other plant matter you pull from the garden (as long as it doesn’t contain seeds or disease you don’t want spread)

- Specific wood-based mulches like bark or cedar chips (I would only ever choose these over free chips from arborists if a client was extremely particular about aesthetics and wanted uniform pieces of mulch)

- Compost (not as effective at water retention on its own, but is helpful when topped with another mulch option)

- Pine needles

- Grass clippings

- Fallen leaves or leaf mold (make leaf mold by piling up fallen leaves in a dense pile, in a large barrel, or in a yard waste bag, water the pile, and let it sit for a year. That’s it. You can speed the process by turning the pile or by chopping up the leaves using a mulching setting on a lawn mower, but you still have to wait months for natural decomposition to occur).

Note, bare soil is important for ground-nesting insects. As gardeners trying to heal the ecosystem, we can leave a patch of undisturbed bare soil somewhere in our growing space for the creatures who make their homes there.

Plant Selection

There are three ways that the plants you choose to grow can conserve water. The first is through drought-tolerance. We don’t apply this suggestion to food crops as much as to perennials and ornamental plants, because if you want to eat watermelon or celery or cucumber (thirsty plants), you should absolutely grow them if it means you don’t have to buy an imported version. When choosing other plants for your garden, opt for plants that will grow well with the amount of moisture that naturally occurs in your space. That is, go ahead and plant things that like wet feet (like cardinal flower and buttonbush) if you have a permanently soggy place in your yard. If you have well draining soil and no naturally wet areas, stick to plants that can tolerate drought (or are matched to the soil conditions) so you don’t have to constantly irrigate the garden. For fun, here are some drought-tolerant common vegetables: kale, chard, corn, green beans. For even more fun, here are some drought-tolerant native edibles: Jerusalem artichoke, nodding onion, wild black currants, and prickly pear cactus).

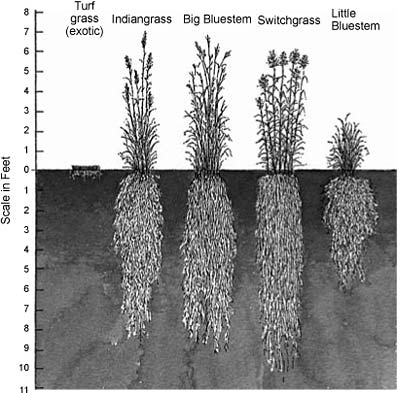

Another way you can conserve water with your plant selection is by planting deep-rooted perennials. These plants send their roots incredibly deep into the ground (comfrey, for example, can send roots 8 to 10 feet deep).

Despite a popular misconception, it is unlikely that plants use these exceptionally deep roots to access water from deep in the ground. Instead, they help conserve water by creating channels in the soil through which water can seep. Deep-rooted perennials aerate the soil, prevent erosion, and help water soak deeply into the ground instead of running off to the lowest point.

Image source: NBGI, November 2016

Plants can also be used as a living mulch, conserving water in the same way as non-living mulch. Plants like wild strawberry and calamint sprawl across the ground in a mat that reduces soil evaporation. Living mulch is useful around larger perennials like trees and shrubs, and should not be planted around other shallow-rooted plants that do not like competition.

Drip Irrigation

You only need to turn on a sprinkler on a hot day and observe the spray to see some of the water evaporating before it hits the ground. Drip irrigation comes in different setups, but essentially it’s just a tube or hose with holes in it, and pressure-regulated water runs through it at a rate that slowly drips out onto the soil. You can have fancy drip systems with emitters spaced exactly at the base of each plant, or you can use a cheap soaker hose. The options (and the price points) are vast. It is nearly impossible to set up drip irrigation in an already-lush garden, so plan to install this kind of system when the garden is dormant for winter.

Note that some people prefer sprinklers because they mimic rainfall. Some of the life in a garden (birds, for example), appreciate a sprinkling every now and then. Fungi that can harm your plants like it too, though, so I encourage drip irrigation (or watering right at the base of your plants using a hose) over a sprinkler.

Shaping the Land: Swales and Hügelkultur

Swales and berms are a permaculture design method that captures water on its way down a sloped surface. Trenches are dug on contour (that’s the swale) and backed on the downslope side by a mound of soil (that’s the berm). You can plant in a swale, or fill it with rocks or gravel to make a garden path. Berms become excellent places to plant things like fruit trees and guild plants (symbiotic plant species, common to permaculture design). As rainwater flows down the slope, it is captured in the swale, held back by the berm. This pause in its downward trajectory gives it time to soak into the ground. Plant roots help stabilize the berm and further prevent erosion. Swales and berms can be made on steep hills or barely noticeable slopes, they can be long, stretching across an entire hillside, or short, in the style of “fish scale swales.”

Another cool method for retaining moisture in the garden is hügelkultur. It’s a method that may not be as easily applied in small-scale backyard gardens, but worth mentioning just in case. A hügelkultur garden is a pit of large logs and other organic debris that is covered with soil. The logs act as a sponge, holding onto water and releasing it as needed. As a bonus, it can be designed as a berm and swale to capture water. I filled my raised beds with large logs underneath the soil which has a similar effect.

Each of these water conservation methods can be used alone or combined for the ultimate water-efficient garden. If you’re planning a new growing space, I’m happy to help you incorporate water conservation methods into your design. Check out my consultation packages or contact me for more information.