Low-Effort Homegrown Food:

A Guide for Busy People

If you want to grow food but are also juggling work, family, social obligations, and a million little tasks that keep you going from dawn till dusk, A) you’re not alone, and B) you could use a guide to help you grow what you have time for.

Growing your own food can become as intense as subsistence living, if you want it to. In this lifestyle, there’s always something to plant, harvest, or preserve, every single day of the growing season. Alternatively, you can opt for a more self-sufficient garden style. This guide will help you make decisions around what to grow, and importantly, how to grow it, so you don’t have to commit to tending a garden every day.

In this guide, we’ll go over four main factors of the plants you should grow to get a low-effort harvest:

1) Annual vs. Perennial;

2) Ease of Planting and Care;

3) Harvest Requirements; and

4) Soil Requirements.

I’m also going to give you some hot tips to keep your plants watered without needing to be outside with a hose every other day.

Crop Selection for Low Effort Harvest

Annual Vs. Perennial

Annual plants are those the gardener plants from seed or seedling in the spring and sees them through their entire lifecycle in a single growing season. Even if you harvested nothing from an annual plant, it would die at the end of the growing season (usually at first frost).

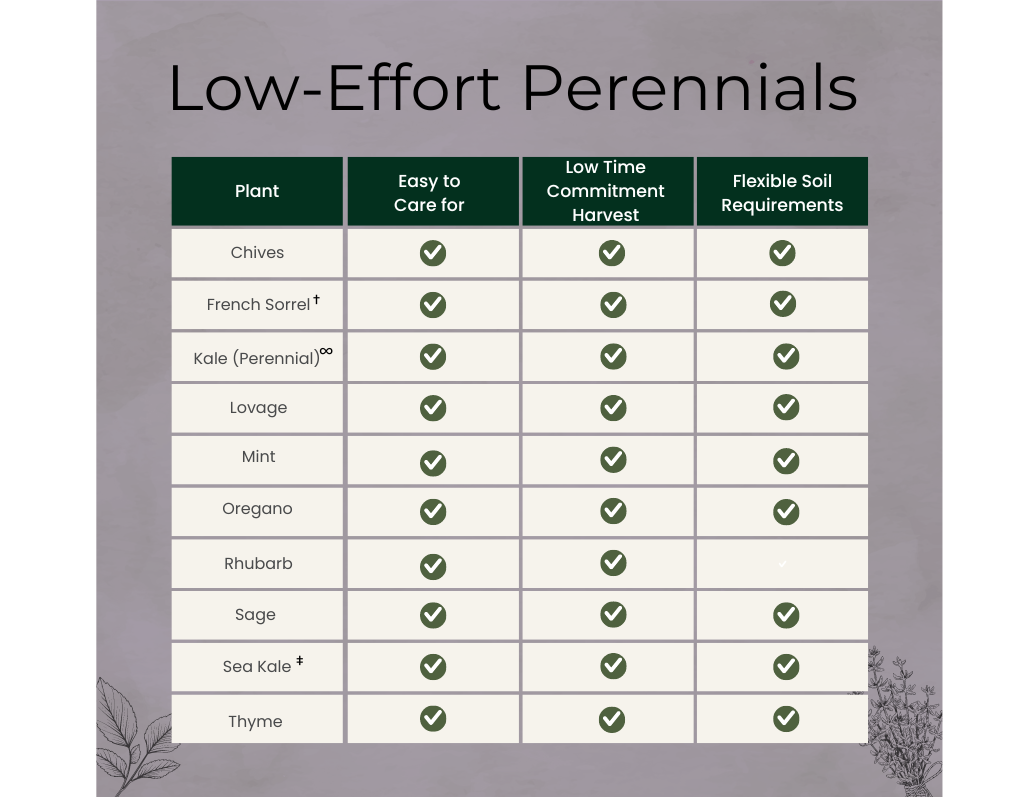

A Perennial is a long-lived plant. In Northern latitude climates, perennials go dormant in the winter and regrow in the spring.

Technically, there’s another category called biennial. Biennials require two years to carry out their life cycle. In year one a plant grows from seed. If left in the ground, the plant goes dormant in winter. When it breaks dormancy in its second spring, it develops seeds. After those seeds have dispersed, the plant’s job is done and it dies. Any biennials recommended in this guide are harvested for consumption in their first year, so we’ll throw them in with the annuals for our purposes.

There are low-effort annuals and perennials, but perennials are arguably more self-sufficient. The only real downside with perennials is that it takes several years to start getting a worthwhile harvest from most perennials. Fruit trees, for example, can take 5 years from planting before putting out a sizable amount of fruit. Asparagus needs to be left untouched for 2 to 3 years before you can take your first few spears. As we’ll touch on later in the watering tips, perennials require very little (if any) watering beyond their first year.

Annuals may be more hands-on to grow, but the ones I’ve listed in this guide are so low-maintenance that they’re about equal to perennials. Annuals are also a better bet if you are growing in pots (perennials usually need to be able to send their roots deeper than pots will allow, though there are some exceptions), or if you think you might be moving in the next 5 to 10 years.

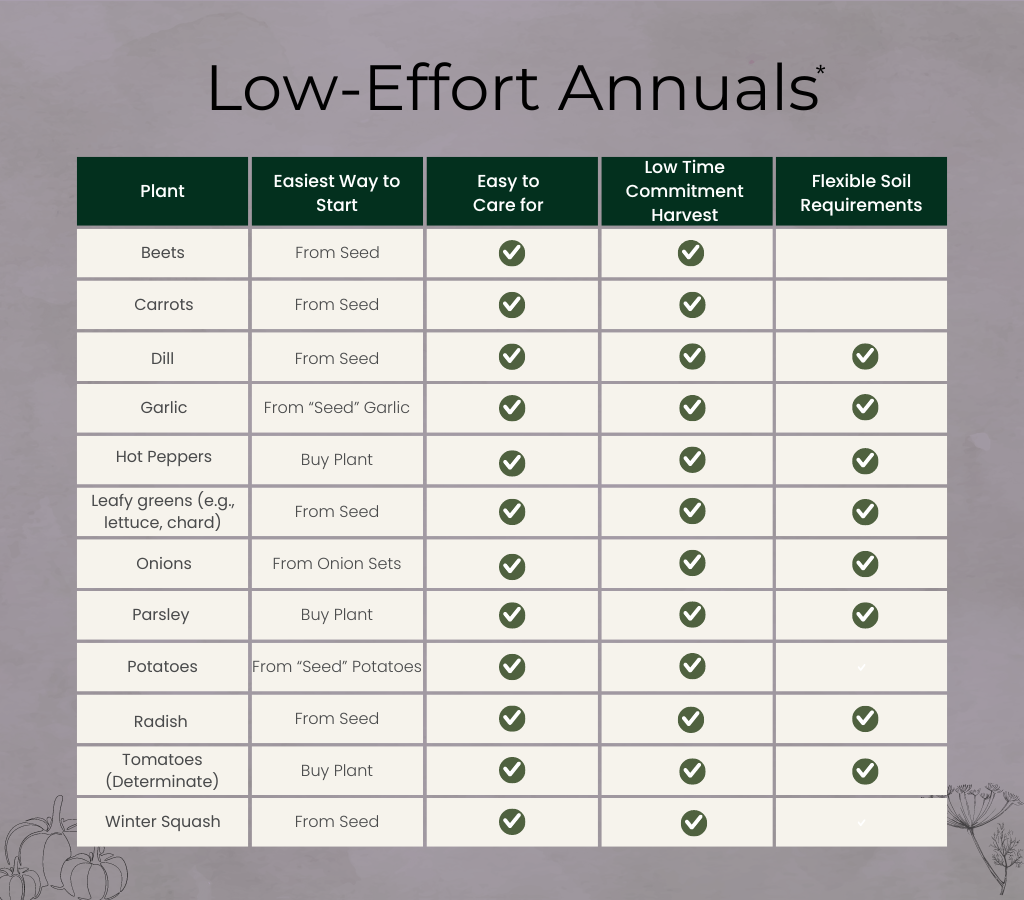

Ease of Planting and Care

There are some food crops we can classify as good for beginners, and others that are closer to “expert level.” Low-effort gardening usually requires easy-to-grow plants, so the tables below list easy crops.

Some are easy to grow from seed directly sown in your garden. With these plants, you can pick up a pack of seeds, follow very basic sowing instructions on the seed package, and have pretty reliable growth. Other easy-to-grow plants are best for beginners to buy as seedlings. They may technically be easy to start from seed, but require an indoor setup with grow lights to grow those seeds into healthy seedlings. I’ve included these in the table as well, indicating that they’re easy if purchased as seedlings.

At the end of the day, the weather has more of a bearing on your growing success than you do, so don’t be discouraged if your beginner neighbour was able to grow giant, white heads of cauliflower while your basic lettuce immediately went to seed.

Harvest Requirements

The food we grow can also be categorized by how it’s harvested. The most time consuming plants need to be harvested regularly, often daily, or the crop will spoil or the plant will stop producing. Things like green beans, peas, and tomatoes fall into this category. The plants that work best for the self-sufficient garden can either be harvested a bit at a time as needed, or harvested all at one time but with some wiggle room around that harvest date. The table below indicates which easy-to-grow plants fall into these latter two categories.

Soil Requirements

Different plants like to grow in different types of soil, but some are happy in a range of soils as long as it’s not too compacted or depleted of nutrients and organic matter. None of the fruit or vegetables in this guide will be happy growing in developer fill, heavy clay, or on a sandy beach. However, some are less fussy about soil type than others. Plants listed in the table below as having flexible soil requirements are generally less fussy. If this box is not checked, it may just mean you would need to add organic material (like compost) to the soil, or, for root vegetables in particular, have loose, well-draining soil. If you’re growing in raised beds or pots with an imported soil mix, you don’t need to worry about this category as much.

∞ Perennial kale is only hardy to zones 7, occasionally zone 6 if protected. A common variety is Walking Stick Kale.

‡ Sea kale is a less common garden vegetable, but the young shoots can substitute for broccoli and is ready in very early Spring.

Hot Tips for Watering

Plants need water – there’s no getting around it. There are ways to get around spending hours a week watering them, though! The simplest trick is to mulch your soil. Chopped straw is an ideal mulch for annual vegetables, and wood chip mulch is ideal for established perennials (like fruit trees and berry bushes). Adding about 2-inches of compost under a layer of mulch will hold onto the most water while also feeding your plants throughout the season. Water retention is a big help, but you will still have to supplement the rain to have a thriving garden – ESPECIALLY if you’re growing in pots. If you have a couple hundred dollars to invest and the willingness to learn, an irrigation system is the way to go.

Note. If you plant perennials (e.g., fruit and berry trees, asparagus, rhubarb), the need to water beyond natural rainfall usually only applies to the first year after planting. There may be exceptions if you find yourself in a serious drought, but perennials establish themselves with large root systems that can access more water.

A Caveat on Hands-Off Gardening

It is possible to grow food as a hands-off gardener, but being present in your food-growing space is by far the most effective way to have gardening success. You don’t necessarily have to be toiling in back-breaking labour, though. Just being in your garden as an observer will help you catch pests and disease early, notice if the soil is exceptionally dry, or if the peak harvest window is approaching for any given crop. If you’re able to take a stroll through your garden every few days, you’ll improve your chances of success.

Consider Permaculture

Permaculture is the ultimate form of low-effort gardening. If you find yourself here looking for low effort maintenance but think you might want to invest some up-front time and energy into gardening, look into permaculture. This approach to gardening will give you a truly self-reliant and resilient garden and property. It’s an exciting rabbit hole to go down.

Final Note on Select Crops

Some of the plants above made it into the low-effort category overall, but have some common challenges to be aware of. If you’re prepared with even a little up-front knowledge, you’ll have much better chances for a bountiful harvest.

- Radish. Sensitive to heat – plant early Spring and again late Summer.

- Potatoes. Prefer well-draining soil and regular watering. May need to “hill” your plants depending on variety and planting method (this just means adding soil or straw in a mound around the lower portion of the potato plant as it grows).

- Winter squash. Super easy to grow BUT can be targeted by pests like squash vine borer, squash bug, and cucumber beetles. These pests will kill squash plants either by destroying the stem and roots, or by carrying plant diseases. If you have the space, sow fresh squash seeds every 2-4 weeks in May and June to outpace the pests. When one plant dies, you’ll have backups.

- Carrots. The biggest challenge with carrots is getting seeds to germinate. Keep seeds moist by covering with a board until they start to germinate (check back every 5 days or so for up to a month to see them begin to germinate). Plant in loose soil so they grow long and straight. Compacted, rocky, or clay soil can lead to stunted and forked carrots.

- Onions. Some people say they grow bigger onions from seed than from sets, but the low-effort gardener should definitely start with sets. Sets are just a pre-mature onion that is stalled in the growing process, waiting for you to plant it. You can buy these in any garden centre or box store in the Spring. Just be sure you’re growing a variety appropriate for your latitude – day-neutral onions are appropriate for latitudes closer to the equator where the daylight lasts about 12 hours a day all growing season. Intermediate and long-day onions are meant for more Northern latitudes where the sun shines for more than 12 hours a day during a shorter growing season.

- Garlic. Garlic follows a different schedule than the other plants here. Buy seed garlic (cloves) in late Summer and plant in mid- to late-Fall. Harvest the next summer. See our garlic growing guide for more details.

- Rhubarb. Rhubarb is an easy plant to grow and harvest from as needed. The only catch is that it likes really nutritious soil. If you’re planting it in the ground, mix a bag of compost in with your native soil in the planting hole. Mulch around it with straw or woodchips to slowly add more nutrients to the soil over time. Water about once a week during dry spells for the first year after planting (you can totally ignore it after that). After a few years, though, you will have a healthier plant if you divide the crown/root ball. You can either give away the excess you’ve dug out, or plant it elsewhere to expand your patch.