Plant Disease Management

There is no denying the climate is changing, and with the heat waves in summer, milder winters, periods of flooding and of drought, and increases in atmospheric gases like ozone and CO2, our tender annual vegetable plants are under an increasing amount of stress and susceptibility to disease1. The reality is, we are up against increasing challenges when growing food.

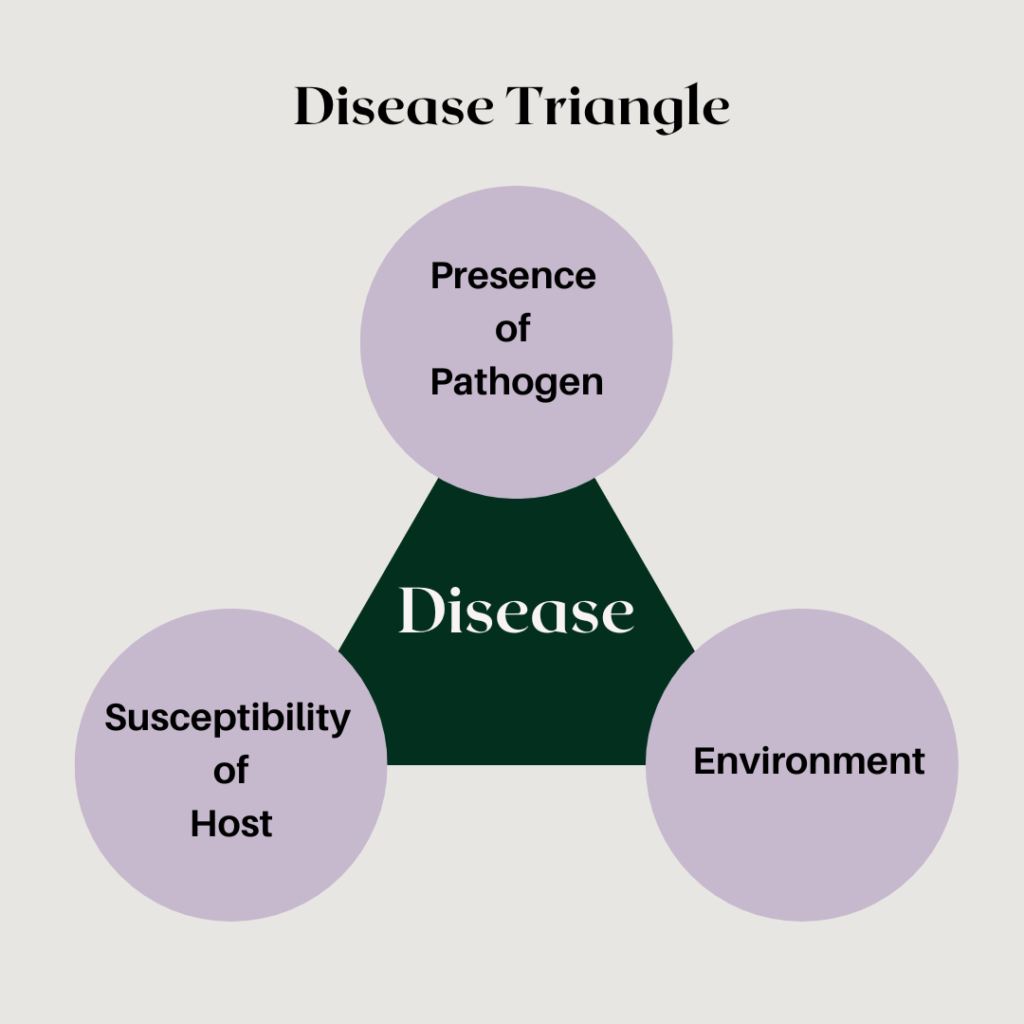

To understand this increased susceptibility, let’s look at the “disease triangle.”

Three things must be present for plants to get sick:

1) the pathogen has to be present (could be fungal, viral, or bacterial);

2) the plant has to be susceptible to the disease (stress increases susceptibility);

3) the environment has to be conducive to the spread of the pathogen.

First, climate change is increasing the geographical spread of many plant pathogens (they are more successful at reproducing in warm, humid conditions). As food growers, we are up against more pathogens – and more virulent pathogens – than we were in the past.

Second, plants are stressed by the effects of climate change, and stress weakens plants’ defenses, making them more susceptible to the pathogens. For example, increased ozone interferes with photosynthesis, making plants weaker and more susceptible to disease2.

Finally, the environmental conditions are generally more favourable for the survival and spread of plant pathogens. For example, some pathogens that used to die off in cold, winter temperatures are now surviving through winter in higher latitudes than before3. Increased humidity and precipitation provides excellent conditions for the spread of fungal and bacterial pathogens.

So, here we are at the precipice of a collapsing food system, and we’re trying to do something about it by growing the food ourselves. But we’re still facing the same mounting pressures as the large-scale food producers. Our little backyard food systems are not immune to the climate-related pitfalls of the larger food system.

Cheery, I know.

Where to Go From Here

1. Plant disease resistant varieties.

This doesn’t mean you have to start planting GMO seeds in your home garden (in fact, GMO seeds are generally only available for commercial farmers). Hybrid varieties of almost every vegetable and fruit have been selectively bred to resist certain diseases. This selective breeding is like giving nature a helping hand by ensuring the strongest plants produce lots of offspring. Once the seed producer selects parent plants with advantageous traits, they manually cross-pollinate the two different varieties. The mother plants then produce seed (like any other seed-producing plant), and those seeds will grow hybrid plants. Using careful trait selection and manual hybridization, seed producers can assure us that their cucumber variety, for example, is resistant to cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), or that their tomato variety is resistant to blight. It’s easy to find disease resistant seeds through most seed companies.

2. Focus on growing strong, healthy plants.

Once the plants hit the garden, there are ways to help them combat disease. Healthy soil is capable of growing healthy plants, just as you and I need proper nutrition to maintain strong immune systems. Amend your soil with compost to promote a diverse population of microbes and fungi. Keep your soil hydrated by watering deeply when needed, and mulching to retain moisture. Remember the disease triangle – stressed plants are more susceptible to disease, so help reduce their stress.

If you have the choice between healthy and unhealthy looking seedlings, plant only the healthy ones. This may seem obvious, but I bet you’ve planted unhealthy seedlings before (I know I have). Whether we start the seeds ourselves or buy young plants, many factors can weaken young plants before they even make it to your garden. Pests like white flies or aphids weaken them by eating the leaves, stems, and roots. The plants may be leggy (long, spindly, and weak-stemmed) from having inadequate light. They may become root bound in pots. If you have the choice, don’t plant weak seedlings. They’ll only be more susceptible to disease.

3. Remove disease vectors.

A vector is something that enables the spread of disease, like insects that carry pathogens to your plants. Aphids are possibly the worst offender. These pinhead-sized insects transmit more than 150 different plant viruses to a huge range of plant species. Another common offender is the cucumber beetle (they come in a striped and spotted form). This small, flying insect nibbles away at your cucumber, squash, melon, and pumpkin plants, spreading bacteria that causes bacterial wilt and the viruses that cause cucumber and squash mosaic virus. There is no saving a plant with either of these diseases.

The simplest way to protect plants from insect disease vectors is to cover them with insect netting from the time you plant them. For plants that require pollination to fruit, you’ll need to remove the cover when they’re flowering, or hand pollinate.

If you don’t like the look of insect netting all over your garden, you can physically remove insect pests. Aphids can be removed by pruning out infested plant parts or spraying the plants with a steady stream of water from the hose. Larger insects, like cucumber beetles, can be hand picked and dropped into a container with soapy water. Most bigger insects tend to slow down and become easier to catch at dawn or at dusk.

Helping to restore a balanced ecosystem can keep many pest insects in check, but this is a long-term effort and isn’t always possible if you’re working with a small backyard surrounded by pavement or mowed lawns. If you can, plant diverse native plant and tree species in and around your food-growing spaces. Provide wildlife habitats in the form of water sources and piles of debris (logs, branches, leaves). We’ve recently had the joy of watching a family of chickadees raise multiple clutches of young in our garden – these birds catch 6000-9000 caterpillars to feed a single clutch of babies4. Consequently, we’ve barely noticed those green cabbage loopers in our brassicas this year.

4. Use cultural practices that reduce spread of disease.

Cultural practices in gardening are the ways a gardener manages their plants. One example is the way we water. We can’t control the humidity in the air or the amount of precipitation we get, but we can control how much we contribute to that moisture (or not). Ideally, the gardener will use drip irrigation or hand watering at the base of the plant. Watering the leaves of your plants creates excess moisture around the leaves which acts as a disease vector (particularly for fungal issues).

Another example is pruning. Some food crops, like tomatoes and squash, can get so thick with foliage that the fungal and bacterial diseases spread like wildfire from leaf to leaf. In cucurbits (e.g., squash, cucumbers), dense foliage creates more moist and humid conditions. In tomatoes, pathogens can splash up from the soil onto the lower leaves during rain. You should typically avoid pruning too heavily or the plant will struggle to get enough energy from photosynthesis. However, pruning tomatoes and cucurbits, as needed to increase airflow and remove diseased foliage, can prolong the life of a plant.

Build Climate-Resilient Gardens

We may not be able to stop the spread of plant disease or save all of our plants from succumbing to them. We can do little things, though, to increase our chances of success in a changing climate. We can make our plants less susceptible to disease by planting disease resistant varieties and ensuring our plants have the nutrients they need to be resilient (stressed plants are sick plants). We can do small things to impact the environment around our plants, like preventing or removing insects that act as vectors for disease, using appropriate watering practices, and pruning certain plants with dense foliage. At the end of the day, we can never win in a battle against nature, so we instead need to learn to side with her. We can give nature a helping hand to restore balance, one garden at a time.

- Waheed, A. et al. (2023). Climate change reshaping plant-fungal interaction. Environmental Research, Volume 238, Part 2, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935123020868 ↩︎

- Mondor, E. & Tremblay, M. (2010) Global Atmospheric Change and Animal Populations. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):23. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/global-atmospheric-change-and-animal-populations-13254648/ ↩︎

- Lahlali, R. et al. (2024). Effects of climate change on plant pathogens and host-pathogen interactions, Crop and Environment,

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2773126X24000212 ↩︎ - Tallamy, D. W. (2019). Nature’s best hope: a new approach to conservation that starts in your yard. Portland, Oregon, Timber Press. ↩︎